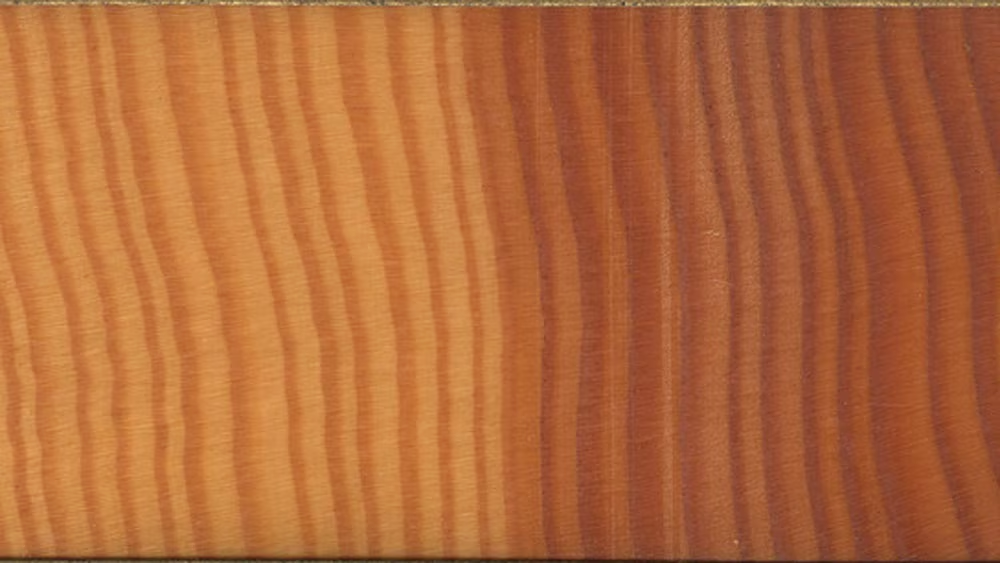

Wood species vary in color (pale yellow versus rich reddish-brown) and characteristics (knots versus clear grain), and the one you choose will play a huge part in your timber home’s identity.

But it’s not just their looks that will make an impact — the moisture content within the wood fibers can influence how they will perform once the frame is cut and assembled. We’ve spelled out these characteristics so you can understand the role they play in your timber home’s evolution.

Green timbers

Green timbers are fresh from the forest. They have a high moisture content (25 percent or more), making them easy to craft since they’re softer to cut. Green timbers also are the most economical option because they typically require less advance handling and preparation.

However, green timbers have a lot of drying to do — and all of it will be done after they’re crafted into your home. As it dries, green wood can check (crack), particularly when the weather turns cold and you turn on your heater, accelerating the drying process. Fortunately, checking shouldn’t impact the structural integrity of your home, if it’s properly planned and built. Timber framers who work with green wood know how to adapt their joinery to these conditions.

Dry timbers

To reduce the amount of movement a constructed frame experiences as it settles, timber framers employ a variety of wood-drying methods, from baking them in a kiln, to allowing them to air dry, to harvesting trees that have died while standing in the forest.

Large kilns will dry the timbers over the course of several weeks, reducing the moisture content to approximately 18 percent. By contrast, air-dried wood must rest in log yards for months — even years (depending on the thickness of the timber) — to reach similar moisture levels.

Because of this additional investment in time and resources, prepare to pay more for both types of dried timbers than you would for green wood.

Standing-dead timber is dried by Mother Nature. It’s harvested from trees that were killed in the forest, causing them to dry while standing. With its low moisture content, this type of wood is super stable and less prone to checking or twisting than green timber. Standing-dead timber also costs more because it is selectively harvested and, therefore, less plentiful than other options.

Upcycled timbers

It’s hard to believe now, but some of the most beautiful timbers around used to be considered “damaged.”

Take reclaimed wood for example. It wasn’t that long ago when many people wouldn’t dream of building their home from the remnants of a dismantled barn, a centuries-old factory or railroad trestle. But not only do these types of timbers add instant provenance to new home construction, they’re an eco-conscious choice as well.

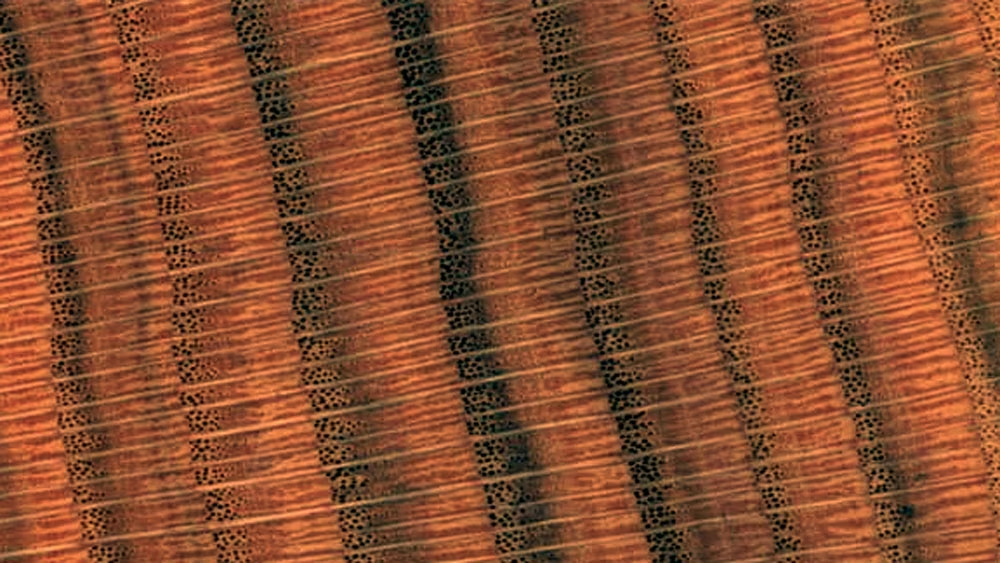

“Blue-stained wood” is another now-sought-after option that used to be a no-go in the not-so-distant past. The distinctive coloration comes from microscopic fungi in the sapwood of a tree (usually pine) as a result of a bark-beetle infestation that kills the trees. Don’t worry — by the time the wood makes it to a home, the bugs and fungi are long gone; but the colorful tint they leave behind makes for a gorgeous wood treatment.

All these options are well seasoned, making them extremely hard and stable. But because they’re more difficult to obtain, companies charge a premium for them.